It’s October, and here at Biff Bam Pop! that means 31 Days of Horror, a month-long celebration of all forms of the macabre in pop culture. “The Ten Percent” wanted to kick things off with an exploration of just why horror matters, along with recommendations for you when you need a good scare. I was especially pleased to step aside (I hope gracefully) to allow someone with far greater expertise to take your hand for a trip down this shadowy lane.

To my knowledge, Kristopher Woofter is not, in fact, a creature of the night, although you can be forgiven for making that assumption. As a bona-fide horror scholar, Kris has spent more time thinking about horror than I’ve spent thinking about chocolate. I approached him, hoping honestly to maybe get a quote and maybe a list of indispensable favorites. Instead, Kris very generously wrote the eloquent column that follows. If you have any interest in “ghoulies and ghosties and long-leggedy beasties and things that go bump in the night,” Kris is someone you’d like to know. I especially encourage you to check out Montreal’s Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies, where Kris serves as co-coordinator. Over to you, Kris . . .

October is the month when everyone’s focus turns to horror—that dark genre that gives us space to air out our innermost fears and desires. This darkening of the collective mind is not solely due to the coming of the carnivalesque celebrations of Hallowe’en, or the Day of the Dead. As the burnt oranges and blood reds of autumn gradually to fade and darken to give way to the damp blackness and decay that inaugurates November, our thoughts turn inward—to the comforts and terrors of our domestic spaces, and to the similar comforts and terrors of our own secrets. For some of us the horror genre is something of a way of life—it colors us our world through a glass darkly, deepening our thoughts about humanity, reality, morality, and the power of the arts to move us. Horror gives us a place both to celebrate the “imp of the perverse,” as Poe called it, and to subvert some of the most oppressive forces that dictate our lives like invisible puppet masters, that invade our dreams, and that plague our individual and cultural consciousness.

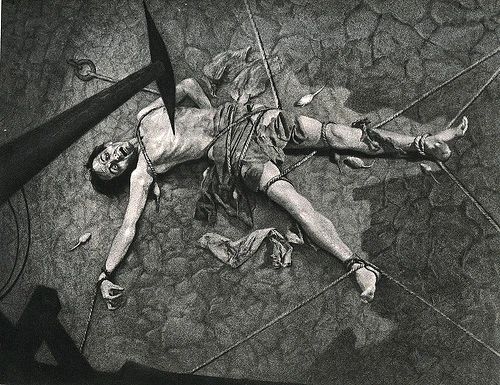

My love of horror developed early. I was always intrigued and terrified by shadows and darkness. When I was 9 or 10, while rooting through a box of my mother’s old college books, I stumbled upon a 1970s bright-orange-colored paperback collection of Edgar A. Poe’s Selected Tales. Under a bare light bulb that would have served well to expose the grinning visage of Norman Bates dressed as “Mother,” I read “The Pit and the Pendulum,” a tale of political persecution that derives its horror from embedding the reader deeply within the perspective of its narrator, who finds release from a razor-sharp descending pendulum only to become lost and crawling around in the darkness. This experience spawned a solid year of reading nothing but horror, as I sought to recapture this experience.

Horror works bring us here—to the edge of the pit. They ask us to think about life, death, sex, the body, and about the power these things wield in our world, through unsettling emotions like shock, anxiety, terror, horror, and dread. In this sense, horror isn’t (as many would have it) merely an escape valve for airing out or exploiting a culture’s dirty wishes. It confronts us with those uncanny truths that we keep buried in the attics and basements of our psyches. It shocks us with an awareness of our world and our place in it.

Those of us who find a seemingly paradoxical pleasure in such confrontations are responding not just to a cathartic release, but to the aesthetic of horror. The horror work is beautiful, full of shadows and dim, expressionistic suggestions of our world—shades of the real tinted by our need to see beyond them. Horror is about this “beyond-ness.” It derives its beauty in many ways from the feelings it can generate from excess, ambiguity, transgression. Horror trespasses across borders, and into forbidden territory to celebrate the irrational as one of the ways that we come to understand the world.

During this season of leaf-caked sidewalks and leaden skies, jack-o-lanterns whose smiles wrinkle into grimaces within a week, and abandoned scarecrows standing guard over wastelands of rotting harvests, take some time to contemplate your own relationship to horror. (Remember: denial of any such relationship is only another kind of relationship.) Maybe one of the following ten selected horror themes—or the films I have attached to them—will introduce you to something about horror that you haven’t thought about before. The list is suggestive, not exhaustive, but it does include 31 films, one for each day of October.

- Horror critiques what our culture and powerful institutions tell us is fair and just.

- Night of the Living Dead (1968, George A. Romero)

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1971, Tobe Hooper)

- Candyman (1992, Bernard Rose)

- Horror ruptures accepted notions around the body and mind. It investigates those people, places and things left outside of—othered by—a circle of “normality.”

- Psycho (1960, Alfred Hitchcock)

- Repulsion (1965, Roman Polanski)

- The Fly (1986, David Cronenberg)

- Horror disturbs our comfort zones and sense of the everyday.

- The Innocents (1961, Jack Clayton)

- The Tenant (1976, Roman Polanski)

- Halloween (1978, John Carpenter)

- Horror is beautiful.

- I Walked with a Zombie (1943, Jacques Tourneur)

- Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio) (1960, Mario Bava)

- Suspiria (1977, Dario Argento)

- Horror encourages our curiosity, but turns that curiosity back upon us. Horror likes to look back at us.

- Dracula (1931, Tod Browning)

- Peeping Tom (1960, Michael Powell)

- Blow Up (1966, Michelangelo Antonioni)

- Blow Out (1981, Brian DePalma)

- Horror makes us feel. It connects us viscerally, bodily, to our world. It shocks us.

- Les Yeux sans visage (Eyes without a Face) (1960, Georges Franju)

- Cannibal Holocaust (1980, Ruggero Deodato)

- Trouble Every Day (2001, Claire Denis)

- Horror philosophizes: it asks us to relate to the world regarding those questions we cannot answer, those limits we cannot cross. It asks us to stand alone on the lip of the void. It is sublime.

- The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick)

- The Beyond (1980, Lucio Fulci)

- Martyrs (2008, Pascal Laugier)

- Horror speaks the unspoken: ghosts, hauntings, troubled and traumatic histories, paranoid present-ness, and dread-filled futures.

- The Haunting (1963, Robert Wise)

- The Blair Witch Project (1999, Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sánchez)

- Lake Mungo (2008, Joel Anderson)

- Horror thrills us, makes us laugh, startles us, manipulates us. As Philip Brophy says, it often touches us with a self-consciousness—a sense of “horrality,” a mixture of horror and hilarity.

- Friday the 13th, Part 2 (1981, Steve Miner)

- Final Destination 2 (2003, David R. Ellis)

- [rec] (2007, Jaume Balagueró, Paco Plaza)

- Horror transgresses. It crosses boundaries of taste, law, morality, ethics and civility—not (only) to defy them, but to explore what they deny us.

- Blood Feast (1963, Herschel Gordon Lewis)

- The Last House on the Left (1972, Wes Craven)

- City of the Living Dead (The Gates of Hell) (1980, Lucio Fulci)

Let the horror begin!

“Ten Percent” guest writer Kristopher Woofter is a PhD candidate in Film and Moving Image Studies at Concordia University where he was awarded an FQRSC doctoral research fellowship for his dissertation research involving Gothic realism in horror cinema. He is also a tenured faculty member of the English Department at Dawson College in Montreal, where he teaches courses on the Gothic, the fantastic, and horror in literature and film. He has published work on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and has a co-authored essay (with Papagena Robbins) on the intersection of the Gothic and documentary in the journal Textus, entitled “Gothumentary: The Gothic Unsettling of Documentary’s Rhetoric of Ration

ality” (2012). His most recent work on horror appears in Reading Joss Whedon (Syracuse UP, 2014) and Recovering 1940s Horror Cinema: Traces of a Lost Decade (Lexington, 2015), for which he also served as co-editor. His current research interests in cinema, television and literature include the horror genre, the Gothic, spirit photography, documentary, mockumentary, and pseudo-documentary. Kristopher is also a programmer for the Montreal Underground Film Festival. He has served for nine years as a co-chair for the Horror Area of the Popular Culture / American Culture Association (PCA/ACA), and is a charter associate and secretary of the Whedon Studies Association.

Regular “Ten Percent” writers Ensley F. Guffey and K. Dale Koontz are co-authors of Wanna Cook? The Complete, Unofficial Companion to Breaking Bad, and of the forthcoming Dreams Given Form: The Unofficial Companion to the Babylon 5 Universe (fall 2017). You can find Dale online at her blog unfetteredbrilliance.blogspot.com and on Twitter as @KDaleKoontz. Ensley hangs out at solomonmaos.com and on Twitter as @EnsleyFGuffey.